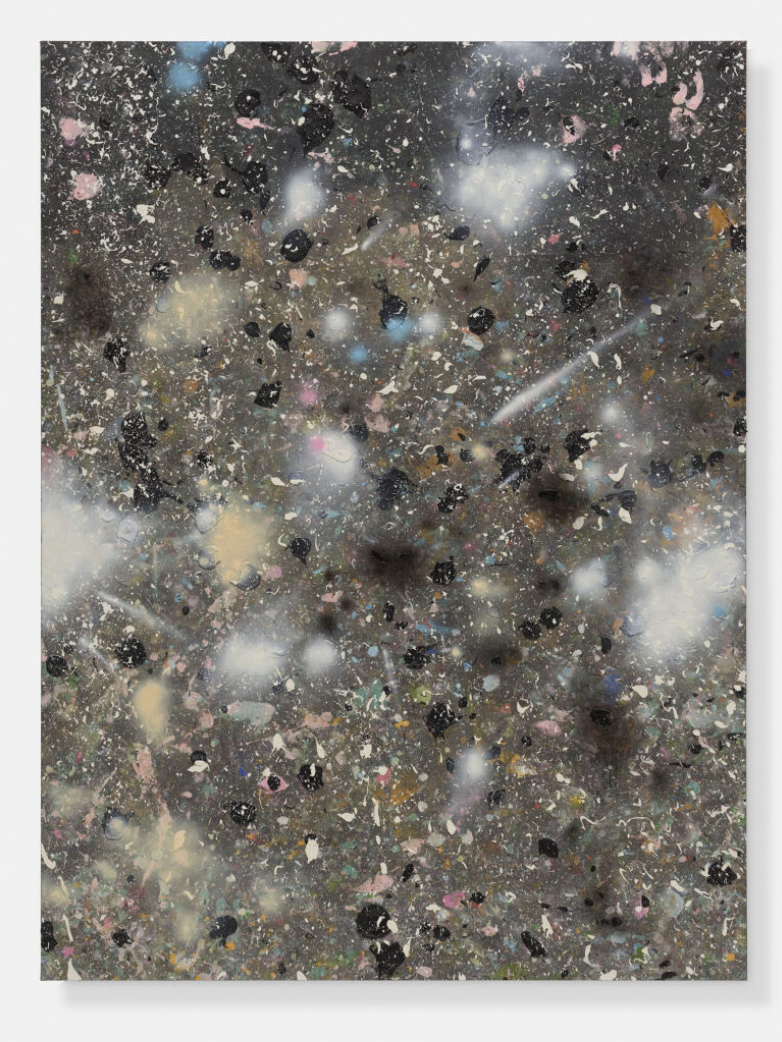

Contemporary art’s least talked about influence. We are still living in Majerus’s shadow. Using paint to depict what we expect from digital interfaces. Why does everyone pretend like we aren’t copying him? It’s like pissing on his grave.

The Unafflicted Life

When we experience agony, we often wish for the time before that agony. But if you remember, the slate was not clean then either. Remember your canker sore? Remember the sprained wrist? Remember the inevitable confrontation with your mother, coworker, or friend? That was the affliction that ruled you last month.

Life is affliction. There’s not some unafflicted life you could be living. This is what life is, trials and overcoming.

There’s always a timeless golden age we set up deep in the past we pretend was without affliction. Childhood.

The human brain is like anything else, if you beat it up bad enough when its forming, those dents carry on. All the time you spend under negative emotions today is the result of a brain that never developed the ways of thinking that can reliably overcome them.

The Tipped Inkwell

Most importantly, if you are experiencing life threatening depression, I highly recommend seeking professional help as soon as you can.

If you read nothing else, please know that no matter what you are thinking or what you are feeling, you are not the only one. In fact, it’s one of the many ways depression doubles its weight—making you think no one has ever been here before.

First of all, why should you read what I have to say about depression? What are my credentials? Truthfully, anxiety has a much bigger appetite for my mind. But I’ve felt the kind of depression that makes you afraid that you’ll consider self-termination about 15 times in my life. I’m 32. I’ve never made an attempt, and I know I would never seriously consider it, so let’s call that category 3 depression. 3 out of 5, I guess. 5 being, like, the big bon voyage. I typically have garden-variety depression that lasts anywhere from 6 hours to 2 weeks about three times a year.

To the uninitiated, depression feels like a lot of things. You’ve heard it described like: heaviness, weakness, fatigue, loss of interest in things you used to enjoy. Let me try to articulate it differently. Depression feels like you got dosed at a party with a drug that robs you of your will to participate in life and you have no idea if the drug is ever going to wear off. It’s like a bad trip but it has lasted for days and everyone said it would only last a few hours.

I say “bad trip” because of the panic it can induce. The loss of desire to live can be so strong that you feel trapped with this unquenchable thirst to escape from yourself and how horrible you feel. But it feels like there’s nothing remotely available for you to use. You can’t get in your car and drive away. You can’t hide from it. You’re always taking it with you. Any second in the day that your brain has time to think, it immediately magnetizes to the depressed vision, the depressed thought, this ineffable sense of pestilent emptiness.

It's not always the painful lack of desire that pushes people too far, it’s the raging desire for freedom.

My analogy for mental illness that can be treated by changes in thought goes like this: our thoughts are like trails in a forest. The more you think these thoughts, the deeper the trail gets and the easier it becomes for your mind to instantly trek down them. For those of us with anxiety and depression, those trails feel like they’re paved in asphalt. You simply cannot help but drive headlong down them.

To add acid to the wound, a lot of people have this attitude toward depression that reveals the belief that you can just “snap out of it”, that with enough willpower, or discipline, you can dust yourself off. Even if this were true, the problem is that willpower is the food that depression is consuming.

Cool, we know what depression is, what do you recommend?

3 immediate hotfixes. These will not cure your depression, but they might help you stabilize yourself long enough to find sustainable treatment. For example, if you don’t stop bleeding out, you can’t get yourself to the hospital.

First and foremost, distraction. When that horrific desire to escape feeling trapped in your mind is eating you alive, you have got to turn your mind off. Let that depression road in our forest analogy get overgrown so it’s harder to go down. There is a point at which your brain is so conditioned to spiral out of habit, that you need to reset yourself.

In 2013, I quit drinking for the first time. My anxiety spiked like a hammer to the face because for the previous two years, I had used a nervous system depressant to smooth out the day-to-day turbulence of life. Without that crutch, normal stressors seemed like monstrosities. I used media to distract me. I had to fall asleep to a movie every night for three months until my brain literally forgot how to leap down the most anxious path in my head. I had to actively keep my mind from thinking. For you, maybe it’s a TV show, maybe it’s cooking something simple. I recommend you be of service to strangers, start a conversation with a random person in public, call family, call friends, and—since we’re getting to it already—when you feel stable enough to speak, let people know what the fuck is going on.

It’s hard to know what comes first: the environment making you depressed or your depression keeping you from seeking a positive environment. In any case, if you have a partner and you haven’t been opening up to them, you gotta start now. Preferably when the time is right, you know, right when they get home from a double shift waiting tables—that should be perfect. Seriously, make sure you ask your person if they can make time for you to share what’s going on. Set and setting makes a huge difference. If someone isn’t ready to hear you, but it comes across like they don’t care, you could feel way worse.

Your family might be terrible, but if you’ve never shared yourself in this manner, I think it’s generally worth a shot. If they suck at listening, at least you won’t be surprised. If you’re worried about them telling you to go to church or eat more fruit or something, honestly, maybe you need to try those things. These conversations with parents or siblings might not make you feel a lot better but you will rest assured that you have made an effort to include important people.

If you haven’t opened up to your friends, do so. I guarantee one of them will know what you’re going through. If not, let them help you distract yourself with going to a show, going out to eat, or hopefully trying to laugh. And if your “friends” ever make you feel bad about sharing your mental state, they’re not your friends. Shit, they might be contributing to your depression.

If all else fails and the people you spend the most time with on a daily basis are coworkers, reach out to them—on a slow day, with the person you find most agreeable. They might even initiate by complainign about something going on in their life in a roundabout way, you know, making a joke out of it when they might be really hurt. This could be a great opportunity to ask them what’s going on. See if you can’t help. See if you can’t share your stuff.

Remember to always give acquaintances an out. Say, “If this is too much, I totally understand. I’m not trying to dump my shit on you. I just need to level with someone.” That way, when you’re sharing, you’ll remove a little concern that they feel stuck there listening to you.

The third immediate hotfix for depression in my experience is sustained, strenuous exercise. I’m talking about a long run, an hour lifting weights, a martial arts class, shoveling your neighbor’s driveway, whatever you have to do.

A quick PSA: exercise is not going to fill the hole. The existential one. The deep dark nameless pit we never talk about. But we’re talking about hotfixes here, not magic, not spiritual transcendence—just plain, adult solutions to problems that need to get stabilized as quickly as possible.

How on earth can exercise help? Get the image of two dudes on a podcast talking about how you just need to lift weights to change your life. Let me advocate here. Exercise takes all the energy currently working to evaluate your self esteem, your guilt, your downward spiral and diverts it to the mental faculties in charge of maintaining your physical performance. In short, when the activity is hard enough, you will not have the energy or time to think about how you feel. For those of you who are not currently dealing with an undiagnosed neural receptor issue that bars chemicals like serotonin from being communicated, hard exercise might make a big difference very quickly.

These three things, distraction, communication, and exercise, can help you gain enough solid ground to start doing the heavy lifting of seeking professional help, which unfortunately can take months to tackle. Between making “new patient appointments” and navigating insurance, the cost, the time, the fear induced by clinical rooms—it’s no wonder your fucking depressed.

If you don’t have a primary care physician, try your best to get one. If you don’t have insurance, many states have services that make primary care or equivalent services affordable. In Colorado there is a service called Nextera. It’s 90 bucks a month, no insurance required, and they can get you access to great doctors. I personally vouch for them. At the very least, they can recommend specialists, prescribe meds, do tests at a cheaper rate, and be a point of contact.

Speaking of meds, who wants their mental stability to be dependent on a pill? I understand the fear. I started Lexapro two years ago and it has worked well for me. I was afraid to start it because I didn’t want to feel better and regret that I hadn’t started sooner. Lexapro has thinned my depression in both frequency of occurrence and the degree of depression I feel. It took some adjustments to dosage, which was painless, and I want to keep taking it.

It might take several different prescriptions altogether to find something that really works for you. But it’s worth the struggle because you’re already struggling. Medication can save people’s lives. Suicidal depression is as serious as it gets. Half of us are taking speed to get through college, so for God’s sake, if you need to try medication, try it. These meds are not going anywhere and they are relatively affordable especially for those of you who are already wasting money self-medicating and making your mental illness worse. If you’ve exhausted other options like major lifestyle changes and creating a better environment for yourself—and you still do not feel better—please consider medication.

Another big solution that turns people off is speaking to a professional. The shrink, the head doc, the quack. Here’s all I’m going to say about it: these people have spoken to hundreds of patients who are saying the same exact things you are. And they have seen what techniques work and what don’t. Tap into their knowledge. Do not go in to speak to a therapist expecting them to be a guru of enlightenment or for some enchanting sentence to cure you. That’s not going to happen and you are going to galvanize your distaste for seeking aid. The solution is in the interaction itself. You are talking to someone who has made it their life to investigate this shit. They will show you, not just tell you, that you are not alone. Your suffering is not unique, it is not strange, it is not untreatable. And, at the very least, it is worth every penny to admit what you are going through and have a professional look at you and say, “No, you are not crazy.”

Life isn’t a game but let's think about it like that for a second. The point of a game is to win. Depression feels like you don’t even want to play anymore because it’s pointless and there’s no way to win anyhow. Read this carefully please. Some of us follow the white rabbit of depression because in its spiral there appears to be some promise of truth. It seems to confirm something we’ve known all along. “I knew I wasn’t good enough.” “I knew I wasn’t worthy.” “I knew it was never going to get better.” “Why should I live life if it’s just going to end?”

In this analogy of life as a game, the “truths” of depression may be truths. They might be the “secret hidden rules of the game that no one else will tell you”. Sure. They might make a hell of a lot of sense. That’s why we keep listening. But listening to depression—letting it construct your worldview in that disastrous perspective—is like letting the opposing team give you a pep talk before you hit the field. You’re going to believe it's not even worth playing. You need to feel empowered by cutting the rope on things that don’t help you win in your life.

If the point is to win—to be happy, to have fun, to make a positive influence, to lessen other people’s suffering, to adopt a dog, to make art, to have a family, to be good to people—how the fuck are you going to win by listening to depression?

If you got here via IG and you would like to reach out, please don’t hesitate. Thanks for reading.

The Difference Between Fine Art & Illustration

I used to think the dependence on line was the biggest differentiator between fine art and illustration.

Then I thought it was the utility. Illustration is a tool to depict a vision, decorate a web page, accompany words for emersion into a story or article. Fine art’s only official utility is to be useless for anything other than appreciation. It’s a unique object in that way. Unofficially, of course, fine art is extremely useful for increasing wealth for collectors.

The only difference I can come up wtih that holds up to scrutiny is a contextual difference.

A piece is fine art when it is in a gallery, museum, or collection or made with the intention of showing in these contexts.

A piece is illustration when it is almost anywhere but a gallery, museum, or collection.

Christian Robinson immediately comes to mind.

Christian Robinson makes fine art that is often used in illustration contexts like children’s books.

Take a long look at Robinson’s work and tell me it isn’t fine art.

If it didn’t depict kids, cute animals, etc, lets say those smiling faces were erased, would it not be incredibly well-considered abstract art?

His education oozes off the page. He knows exactly what he’s doing and you can see his links to art history clearly on every page.

Anti-Pictures

Depicting something without directly representing it is the greatest challenge in abstraction. But it is where all the treasure resides.

We have represented everything we can see in every possible way. Representation can only be satisfying for the artist. It can no longer speak for beauty.

The only thing left to represent with paint are the aesthetics that AI and future screens have yet to show us.

If you notice, the contemporary trend is to represent through paint what was only possible through digital interfaces. Pixels, LEDs, glitches. This is not as much a breakthrough for hyperrealism as it is meatless innovational scraps tossed to the technically dependent to torture into representation.

Ideas, like “the end of an empire”, are groundbreaking feasts for conceptual painting as well as a wellspring of fresh content for the non-picture painter.

What does end-stage capitalism look like? What does Anarchism look like? What does the world look like without beating it into the viewer’s eyes and insulting their intelligence with repackaged figures? Does a new gimmick of style really show us something different when it is still playing within the bounds of representation?

Ultraviolence, chimeric nemeses, infant religions unaware of their religiosity, holy war, resistance, illegalism, iconic iconoclasm.

There is so much beauty has yet to be in this world.

What is it?

There are so many ways to approach answering the question of “what is art” that it can paralyze you in freedom.

I think the reality is we don’t have a unified answer. We know it when we see it. We know what is trying to be art, what looks like it was intended to be art. But defining it seems impossible. This is a fortunate thing.

Some claim art is the stuff we make that can exist for no purpose other than its own existence. Others believe art is work that is made to be shown in a gallery or museum—this differentiates it from work that may use all the same mediums and methods but intends to be shown in the NYT to get readers to notice and article.

My tinnitus is so fucking loud right now I can’t even continue thinking about this.

My Favorite Illustrators

My taste revolves around a balance of looseness and preciousness. The first illustrator who struck me with awe and jealousy was Bill Watterson followed quickly by Mike Mignola. I love that so much depth and character is captured with as few lines as possible.

The impressionism found in cartooning intensified by rigidity and austerity is what I seek for my own work. With that, I can tell any story in a style that can communicate all manners of emotion.

Quentin Blake

Mike Mignola

Serena Ci

Tom Hunter

Kyle Ferrin

Armand Bodnar

Bill Waterson

Squabbling Children of Anarchy

American media has officially defined Anarchism as grim disarray, absolute chaos, and lawless abandon.

The history of Anarchism, which I barely know and care little for, is much more sophisticated. Libertarian-Socialism, the classic form of Anarchism was an ideal bridging of characteristics from both schools of political thought. The devotion to civil liberty and the structure and priority of the social sphere as the solitary roles of the state.

When individuals are serious about contributing to any political discourse, this is the Anarchism they are providing.

Antifa, ELF, John Zerzan, black-clad LARPers of revolution—these groups veil themselves in “Anarchism” as a power emblem, enforcing the extreme, hardcore aura that elevates their esteem.

Media is to blame not only for the currently accepted definition of Anarchism but for spawning those people whose actions have contributed to the definition.

See The Baader-Meinhof Complex (2008)

Attractive people doing revolution.

For those at a loss for identity, who wish to be part of something larger than themselves, who have all the misplaced hubris of the youth, Anarchism in this manner checks all the boxes.

But true Anarchism it’s much less sexy, much more boring, and much harder work.

Anarchism is the tendency to scrutinize authority and dismantle authority if it’s found to be invalid.

There is truly nothing more.

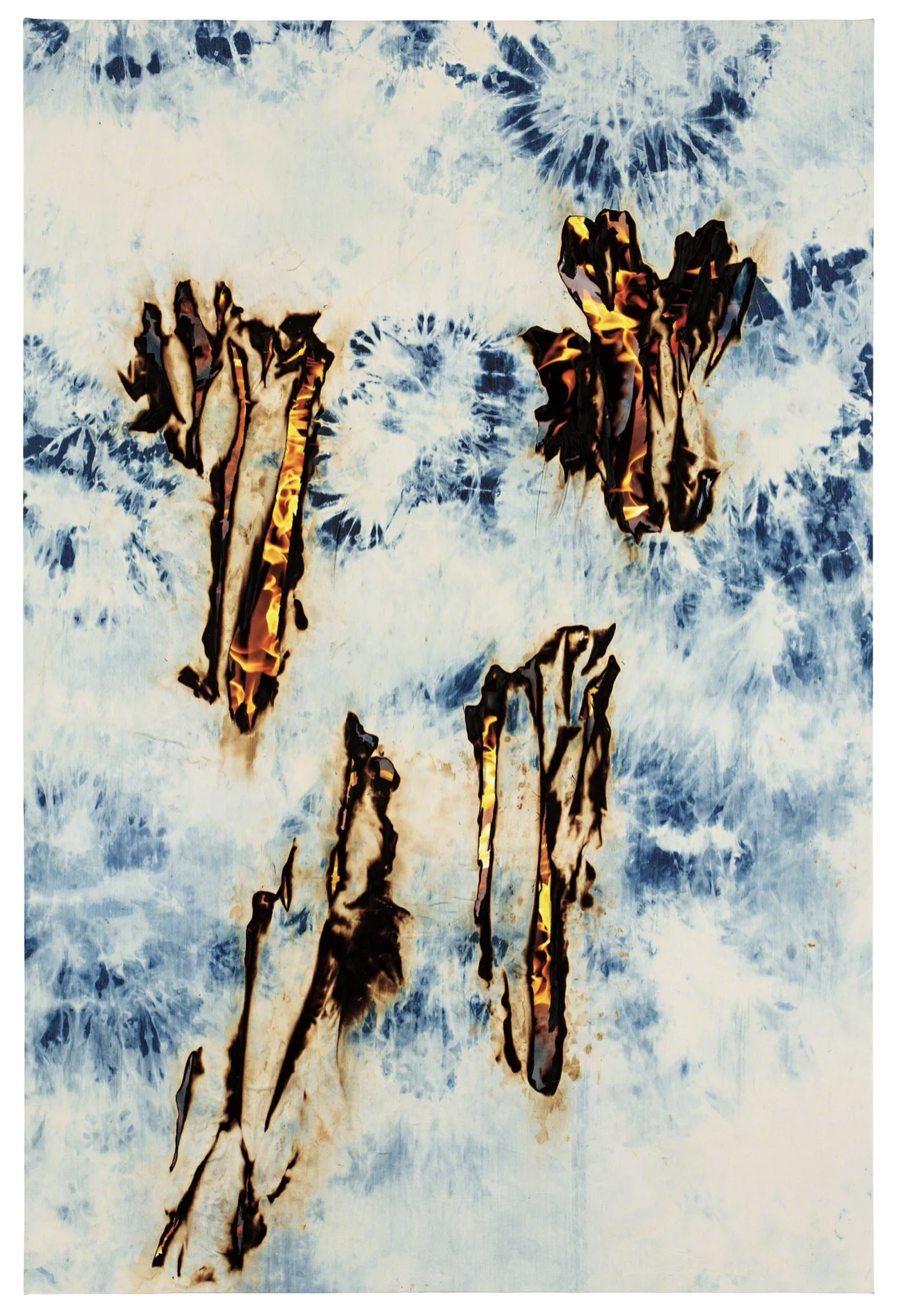

The Beauty of Iconoclasm

Provisionalism, like Wabi Sabi, values imperfection. It resists the seduction of torturing a vision into reality. Instead, it seeks to allow the millions of beautiful moments that arrive unintentionally and accidentally—moments completely outside our control—their own sacred space.

Theoretically, there is a double bind in provisional painting. Attempting to complete something that appears in progress would be fraudulent. A genuine approach would have the discipline to abstain from the correction one’s mind is conditioned to make. To put the brush down when you notice a beautiful moment in the interim of your preconceived notion of finality. I believe Rei Kawakubo claimed that to make a mistake on purpose is no longer a mistake.

Similarly, the ethos of vandalism is unconcerned with realizing some grand aesthetic vision. Vandalism is interested in destruction and its means are chosen as a path to most resistance. It exists squarely on the line between art and life. It is art as a means to affect life. It frequently claims no interest in being art. But paint is often used.

The word vandal has an interesting history. It was a group of people who “ravaged” Rome, Gaul, Spain, and North Africa. A Vandal is someone who destroys what is seen as beautiful by others. Though many cultures have ravaged others, the Vandals’ name was coopted into an act that would carry into all future acts of destruction.

What is the word for someone who finds vandalism beautiful?

In both practices, fate and liminality are accepted as the natural order. One devotes itself to the destruction of finality, the other gracefully allows the destruction of finality to emerge and grow.

My Favorite Paintings

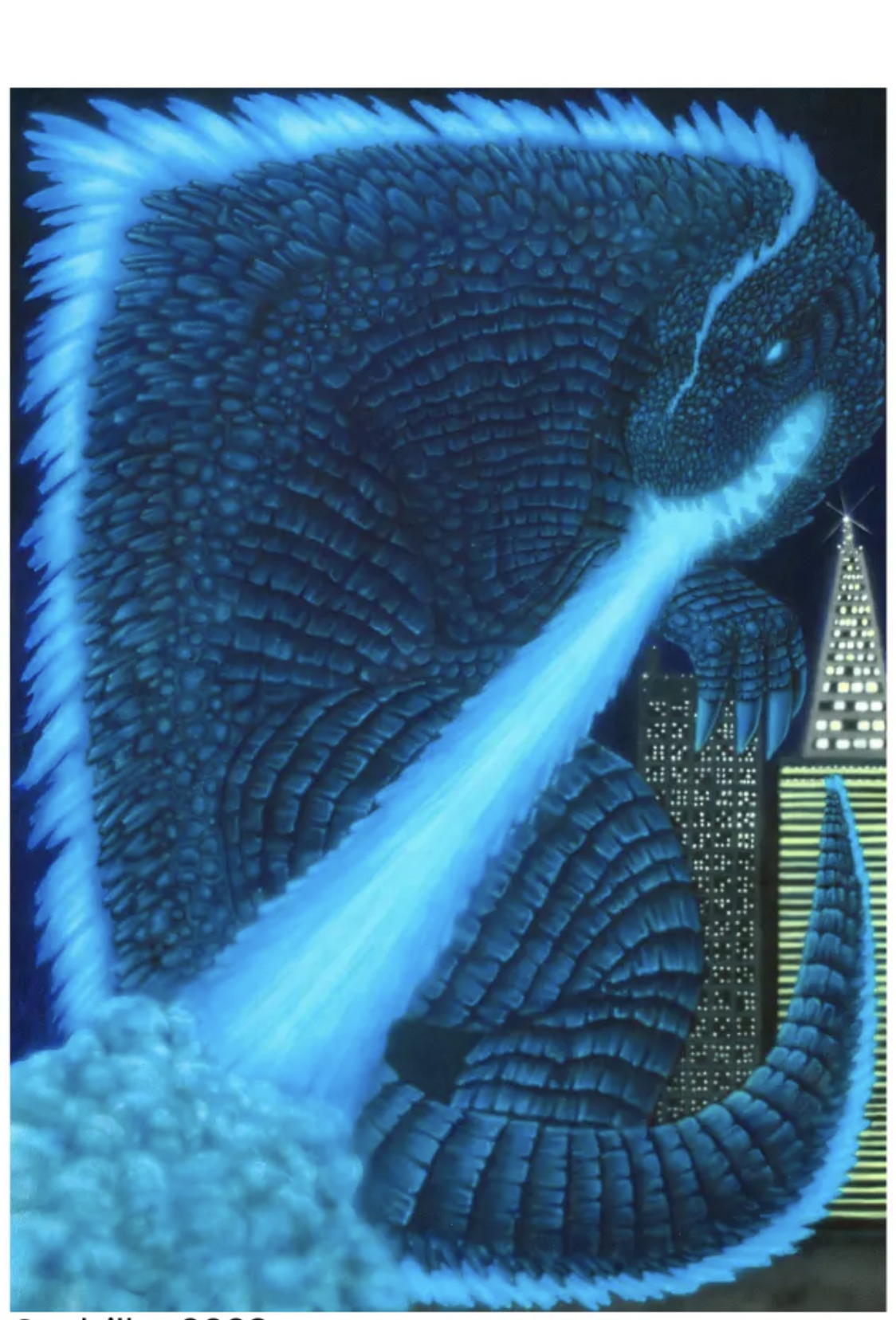

What I seek in a painting in terms of content is something my brain cannot expect to see. An aspect of Futurism surely. Always pushing the medium forward.

Formaly, however, I am unwaveringly attracted to Neo-Expressionism and its contemporary iterations. I am a fan of nostalgia, bright color, devolution, iconoclasm, irreverence, anti-preciousness, meticulous disregard for tradition and a desire to degrade the Institution, all while making a conscious effort to provide the pigs with highly collectible works that are instantly recognizable as the artists signature style.

Devon Troy Strother

Damien Hirst

Sterling Ruby

Robert Nava

Helen Frankenthaler

Misaki Kawai

Korakrit Arunanondchai

Nils Jendri

Vincent Langaard

Haruo Takino

Artist Statements

Each series is made with at least an ethos. Some are born from specific interests.

My return to serious painting began with the “Casa” series. A small batch of acrylic and oil pastel works that depicted my home with a new-found celebratory edge. Bright colors, molcajetes, chili peppers, serape motifs, and the occasional cucuy in the closet. My partner and I are both half-Latin. Together we began to connect with our roots—something we often didn’t think much of until we expressed our similar memories. Being half-Latin and white often leads to a lack of belonging. You have so many specifically Mexican memories, but don’t speak the language. Or you speak the language but never knew your ancestors. Regardless, we found power as well as joy, peace and spiritual guidance. The series is a testament to that time and place.

“Susto” was next and is currently ongoing. The series uses the modes established in “Casa” like serape motifs and bright colors but expresses anxiety and anguish. Many misfortunes have occurred since the Casa series was made. Susto aims to show them. Halloween iconography, such as bats, mummies, boogeymen, and ghosts appear and darker but highly saturated colors show the fear in each piece. As anxiety and anguish are frequent states for me, the series will not conclude anytime soon.

“Exotico” is the most recent and ongoing series to date. It blends my lifelong interests in exoticism and cultural heritage through an initial process of unconscious spilling called Ancestral Recall. The pieces are both provisional and refined and feature many motifs that stem from Mayan and Aztec mythology, Spanish conquest, treasure, gold, oceans, jungles, jaguars, skeletons, curses, snakes, and brujas. I am acutely interested in my own conflicting interests in respecting sacred culture and the Western depiction of the exotic. Films like “Aguirre Wrath of God” and “Apocalypto” as well as the history of looting and iconoclasm of cultural heritage are the roots of my current exploration of the “Exotico” series.

Meta-Aesthetic Entelechism

What is beauty?

Beauty is a force of nature that disciplines beings with the capacity to express it toward its own actualization. In other words, it is the feeling we experience when we witness perfection.

It is present in the arts, but it is also found in engineering, science, finance, and violence.

Beauty is objective. The pleasure or displeasure of witnessing beauty is irrelevant. These qualifiers do not negate the condition that there is a right and a wrong way for the piece to more itself in form. Or, for a graph to be organized, a stock portfolio to be hedged, or a left hook to be torqued.

The experience of beauty, like the experience of odor, is indicative of reality’s noumenonic amness; these experiences act as canaries in a coal mine to those things in and of themselves. Therefore, expressing beauty, and its wisdom of reality, is not merely worth our while, it is an empyrean act.

The meta-purpose of art is not to gain personal pleasure or communal good from engaging in meta-aesthetics but to allow beauty to be actualized and expand its scope and its insights. In other words, the meta-purpose of art is to be a vessel for the entelechy of beauty.

How can beauty be more than eyes and beholders? Because things emerge and things persist regardless of voyeurs. For example, “Sandbars in a river and the stream itself collaborate in persisting as themselves” (Marilynne Robinson Grace & Beauty).

However, even in the exquisitely designed machinery of torture, beauty is at work. The aesthetic archetype should not always gravitate toward actualization.

Ironically enough, beauty is blind. Its disposition is purely to perfect its insistence. Ethics are how we decide whether or not to be disciplined by beauty or let beauty’s daemons die in our minds without manifestation.

Mourning Implication

Living life with loss is worse than losing life.

Why Memes Are Funny

“Me when”

The meme of a movie character acting unaffected while juxtaposed with a title or backdrop of a workplace catastrophe, a car accident, a hangover, a breakup, or any other stress-inducing event, exposes our desire for heroism. It’s funny because it’s true—true that we want to have the power to endure stress without feeling stressed.

Why Music Is Everlasting

We’re stuck in mood’s merry-go-round. Music’s mood is immortally frozen, eternally ready to be imbibed.

Anarchy of Purpose

I often don’t hunger to learn, and I frequently have no interest in mastery. I no longer want to build a legacy through my work. Yet these elements used to drive my productivity. Something fell away in my late 20s and the extremism I had relied on to produce work fell with it. It’s left me wondering, what is Purpose in the arts if not securing preferable labor?

In considering why we work, and why we dream, I’ll admit, I used to just want to be a cool person in a cool place surrounded by cool people. From 16-22 the photographs from Jules de Ballincourt’s interview in Art News formed my vision of a successful future; a big-windowed studio with days talking and making art while being well paid. In my teenage identity crisis, art spoke for me whether I wardrobed myself in other people’s art or my own.

Side note: competition is a purpose by proxy. You get so wrapped up in winning that you forget the whole thing is vaporous. I always work better when my name is on the line, whether I like it or not. There’s no time to scrutinize the competition. It’s very convincing.

There’s little left of that need to be associated with success. I don’t have any identity crises beyond wondering if I should be more concerned that art isn’t as important to me as it once was. The desperation has been worn down by time’s wind alone. Rejection is not to blame. Rejection, historically the kill leader in any pursuit of art, has only driven me further. And what’s been revealed by my years of eroding interest is a very simple desire. The desire for time unencumbered.

Isn’t that the platonic archetype that gravitates all of us? My righteousness would say even those stuck chasing the artist’s life (like Ballincourt’s) are truly just seeking time unencumbered. That’s exactly what’s overlooked in our vision of success: you expect that upon arrival, you don’t have to spend time doing things you don’t want to do.

There’s a lot of pop-actualization wisdom out there to aid the artists’ pursuit. “Believe in yourself, work hard, never give up. Never up, never in.” None of it challenges the premise, which is success. Challenging the idea of success, especially in capitalism, is a separate essay. Let’s just call success here a general improvement of one’s place in life garnered by doing what one loves.

I don’t love any of my mediums. Without exception, what satisfaction I gain by sitting at the word processor, canvas, or production software, is likewise smothered by a feeling of disgust. I get wired easily, ancy, hungry, tired, screen-blind, and paint-sick.

To achieve the perfect space for making work, both physical and mental, I’d have to be rich and msot of my time would need to be dedicated to health and fitness. Only then would there be adequate space for art to be made without detriment to employment, which currently enables what little space I have for art.

Regardless, it seems art is pinned, for those inclined to make it, as a path of less resistance in a labor system. It seems like a simple resolve: if you have to work, make sure you like it. But turning the practice you perform when your time is unencumbered into something that is expected to eventually unencumber your time raises more problems than it’s expected to solve. Muse abuse, despoiling the sacred, losing love for your work… It also has terrible odds of making you rich enough to unencumber your time in the first place.

So should our art remain hobbies instead of golden tickets?

I have no idea what a hobby is. Stamp collectors experience Passion I assume or the giddy joy of arrival. Model makers spend hours on end at their craft, so time spent can’t be a criterion. What qualifier ascends a hobby to a purpose? Grand expectations? Some accolade?

There’s a boundary assumed here in the talk of legacy. People are creatures. We are not—in our lived lives—icons, legends, heroes, or historical figures. For years, assuring my name in history and making myself, my mind, and my work accessible to future humans was a prime mover in my productivity. I didn’t want to be a name on a headstone, I wanted to be a name in future artists’ textbooks.

But I’ve eroded that because the boundary is frail. Those on the other side of immortality, artists who are made into icons, have their creaturehood washed away by becoming an idea. But it is the satisfaction of my creaturehood that I long for now. To be pleased, to feel healthy, to watch a storm roll in with a lover, laughter with family, laughter with friends, knowing a peaceful night of sleep will bookend the day with a cup of tea.

The satisfaction of creaturehood is definitively for me. It serves me here and now. Becoming an icon does not satisfy the artist beyond granting a bit of excitement, which must be one-upped by bigger achievements.

As an icon, I would not be seen but made into a spectacle, an entity of associations, for others in their most unidentified times to use me to identify themselves, my name reduced to a signal for others to show off a sense of style, a sense of taste, or shorthand for academics to peacock their intellect. My whole life, full of habits and fears and pleasures and perversions and acts of kindness would be evaporated into a few choice products that show my slight iteration on a theme as old as time. Grand Inconsequential. Why not have both? The satisfaction of your creaturehood and the becoming of an icon? They are mutually exclusive pursuits. Besides, the world chooses icons. Not the artist.

All of this to say, I genuinely do not see the point in encumbering our time with arts in any professional way unless it’s to make money with more desirable labor. And yet, this cannot be the definition of artistic Purpose.

Martial Entelechy

Martial, meaning, of or in reference to war, and their arts are the entelechy of weaponizing the human body, a dolorimetric discovery of the archetypes in slumber awaiting our fists, elbows, knees, and skulls to find their exact path to actualization. There is an ideal way to strike another person. And there has been since our contemporary form was settled hundreds of thousands of years ago. We’ve had the brain to discover it for at least 200 thousand years. There was no other path but brutal research to finalize the art.

I used to feel appropriative bowing to the mat, now I do it to pay respect to the people who wrote it all down so I could walk into a gym and learn what hundreds of years of bloodshed yielded.

Muscle & Hate

The first interest I had in fitness was as a supplement to alley cat racing in Denver. They were bike races in the city, often in traffic, on brakeless track bikes. The fastest among riders rode every day, so I rode every day. There was no math. There was no routine. I wasn’t interested in exercise. I was interested in adrenaline and speed and how to get more of it.

Four years later, I was about as good as you can get on a track bike in traffic unless it’s your day job. But I had a near miss in Chicago that ended it; this Oldsmobile ran a red and we veered alongside each other up on a sidewalk. A year later, a fellow classmate was pulled under the wheels of a semi. She was killed instantly. I didn’t hear this quote till much later but it sums up why I hung up the bike: “Luck runs out all at once, never by degrees” - Mark Twight. It doesn’t matter how good you are on the bike, chaos is omnipresent.

Lifting was next. I started after college because I’d dropped weight from 155 to 137. How people maintained weight while going to school in the Loop 12 hours a day, working part-time, and bearing the weight of art world expectations is beyond me. After getting back some aesthetic weight, I lifted just to lift. The gains could have continued or not. The point was depletion. I wanted to feel struck by a vehicle. I wanted to be in pain when I slept. As long as my injuries didn’t keep me from lifting, they were welcome.

I’m reminded of a writer friend in high school. She said she bruised her rib during a spat with pneumonia. I asked if it sucked. She said it was painful, but she adored the visualization enabled by the pain. Bones in her skeleton often forgotten or taken for granted shimmered all day like a heat map.

Then the mountains called. They are the supreme church of suffering. The ratio from the simplicity of the end goal to the input required is as extreme as it gets: summit the peak and wage total war on your mind and body to do so. The bar to entry is tricky with mountains. As long as you can get to them, you can try them. But you realize immediately how much they will take from you. Running became the main boot camp to increase my odds. After breaking my legs in, running shifted from supplement to drug of choice. Running was right outside my door, while mountains were hours away and demanded strategy and tactics.

Freedom is the first pleasure in running. Something ancient in that. Triggers to primal flight—but also the joy of exploration fused with the speed at which you can discover. Houses, groves, creeks, towers, bird sounds and quiet air—all neglected in a car—hit you with blunt force on a run. Then there’s the 1st-mile burn, your legs, chest, and back are aching and pinched. After the 5th-mile hump, the body is oiled, the burn is gone, and everything is liquid. You feel like you can live the rest of your life while running. At mile 10 the lungs adjust and they reckon this is the new normal. An entity of momentum. The heart isn’t pounding now, it’s sitting at 120 bpm. Then, at mile 15, the bones begin to show their fragility, and little fissures in the tibias begin throbbing. Every footfall is an aggravated assault. I’d stomp a little harder on the downhills to abuse them. Lactic acid turns to concrete in your thighs. Calves in a perma-charlie horse. You sweat ammonia if you lacked carbs the days prior. I could feel my tissue being eaten while sprinting up the steepest paved street in America. At Zone 5 uphill, the idea of a heart attack is a serious question. It doesn’t beat; it vibrates.

Endorphins can’t take full responsibility for the serenity. Running, the pace, the meditation, the breath, the impact, all of it concerts to the Anarchist spirit. You can run away from anything you can name. You can suffer consensually.

Self-harm had never been an MO for me. Roundabout, sure, via drugs and alcohol. But I never considered self-harm as an end in and of itself, just a tool for proliferating fine art, music, and writing. Exercise showed me how intricate and keen self-harm could be exacted on the body like a lunatic with a scalpel and how splendid the treasure could be. If I ever stretched before a run it was to feel the white thresh of tendons aching to be released.

So much was pent up in me that to deliver pain felt transgressive in a heroic way. The mind tortures the body and the body revolts against the mind. Gains are nothing but time-release confidence with a two-month half-life. Engaging in the torture of exercise breaks the mind that develops concepts like confidence or defeat. The part of your brain that assess your worth transfers all energy to the parts of your brain dedicated to physical maintenance. It can’t possibly give a fuck what you think of yourself. There are no beliefs, there are no inner children, and when there’s nothing left to burn but brain matter, there is no more You.

High on my sweat’s ammonia, my brain vomited this sentiment: When you consider the persistence of muscle, its very existence insinuates terra impersona. The proportionate response to this condition is hate.

Like those victims of trauma in the BDSM community who gain agency in the practice of domination, fitness is a reclamation of pain and suffering. The very spirit of Anarchism is to recognize the authority of pain, and steal the torturer’s devices for yourself, to commit seppuku on your time, with your autonomy.

When The Hero Dies In The Beginning

In Alien Resurrection, we’re introduced to Frank Elgyn, a space smuggler. He is smooth-talking, black-clad, level-headed, hard-drinking, and is the leader of a band of criminals who all respect his seedy smarts. He calls the shots from the beginning but is the first of the main cast to die at the hands of the Aliens.

I believe the writer, Joss Weden, intended to shock both audiences and the main characters by removing the metaphoric ship’s mast at the start of the chaos, thus forcing the group of survivors to have to trust Ripley whose allegiance in the 4th installment is dubious at best.

When I saw Resurrection at the age of 8 by myself, I was cinematically traumatized by the death of this character. I rooted for him to be one of the ending survivors because I liked him, but I was certain he wasn’t going to be the first to die because of everything that made him cool. I didn’t have any notion that such a story device could be possible. It changed the way I percieve character set-up and expectation. It also changed how I view group dynamics and what happens when you remove specific pieces. The dramatic potential is infinite.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how different the film would have been if he had survived longer or been on the ship at the end along with Ron Perlman’s character and Sigorney herself. Below are a list of scenarios:

Elgyn and Ripley hesitantly form an alliance as the most capable of the group in terms of route finding and charisma and strength. But Elgyn maintains his distrust of her allegiance and makes a fatal misstep to remove her from the group before making it to the evacuation.

Elgyn and Ripley initially strife with differences in approach to their planned escape and this causes the group tension as half of them want to trust their captain, but the other half feels like Ripley is better equipped to handle this very unique situation. This scenario likely ends with a full-fledged bond by the end or a sacrifice on part of Elgyn to save her and thus his crew.

I have since been so inspired and hurt by this type of death that I have tried to emulate it in my own writing. In my script, Darkspeed, which centers around a crew of astronauts attempting to use a faster-than-light engine to warp to a nearby solar system, the leader, Jim Vikandless, has all the right answers and soothes all anxieties, but is the first to die when they encounter and inter-dimensional entity named Color.

It almost seems cheap, but necessary to emphasize the tension, to kill off the most well-adapted character when the shit hits the fan. Now we are battered by the circumstance and the lesser of us must grow relationships and force from themselves the solutions when the God/Father figure is eliminated.

I’ll never forgive nor forget what Joss did.

The Academic Painting Critique

I once had a highly successful Chicago painter as a senior painting professor lead his critiques by making us guess what he was going to say next. I think he imagined himself a zen master or so above the adjunct role that he was validated in wasting the 400 dollars of tuition we paid per class. He stated simply, “there will be no painting in this class. Painting is done elsewhere and here we will discuss.” These classes were seven hours long.

I packed my canvas and bars and left dramatically. But even in the classes where we painted with a professor’s attention and knowledge and skill being bestowed upon us as we worked, which is what I wanted, the critiques at the end of the week were no more valuable.

Take the foundations of the critique: who is there to give criticism? A professor who is most likely successful, which is at least something. And a group of 20-year-olds who grew up in Dubai, Macau, with trust funds that would leave you slack-jawed, and whose parents didn’t scrounge, save, and cripple themselves with loans, but who sent their offspring to art school to get them out of the house for 4 years. These dummies could eventually become darlings, sure. Your art world constituency. Most likely not. Their thoughts and words were often useless.

The most common audience for an emerging artist to expect to have is the local art sympathizer, an enjoyer, maybe even a dilettante who goes to as many shows as they can, has no artistic profession, or who may even have money and surveys the scene for a decoration for them or their boss. These are the first audience, the most important audience, for any breakout artist. But their sensibilities are nowhere to be found in the academic critique.

What is found are word salad regurgitations of the recent post-structuralist PDFs handed out in elective classes that week. Deleuze, Foucault. “Knowledge” shat out 50 years ago and worshipped as if it was the latest philosophical contribution. There is also brain-dead, Vyvanse-induced, or hungover silence. Silence you can hear the laminate floor shifting in. No one has anything to say. No one cares about your art. They only care about theirs. Remember, they are the next hero. Not you.

You’re staring at a realism painting of a life jacket. A finger-painted mess of shit brown. A painting on cardboard of numbers. With excuses that end in “isms” that justify the work. Once a gal passed off her last-minute butcher paper painting claiming it was “post-colonial”. This goes on for seven hours straight.

Once a kid made a painting that looked exactly like the wall it hung on. Another threaded shoe laces through a loaf of bread, titled it “loafers”. One had a grocery bag tied to the wall with a fan on to make it dance. There were either one-liners or our best attempts at copying what we thought was contemporarily expected by the fine art world. This spurred my coining of the genre, “Looks Conceptual”. You know the stuff, a cinderblock in the corner, a metal pipe leaned against the wall, chain link fence blocking in a bucket with an iPhone playing some sound. Stretcher bars with no canvas, canvas with no stretcher bars.

The most spine-liquifying aspect of the academic critique is how precious we all act with our art. Treating it as highly-considered and delicate. When we answer criticism with, “I think I like that about the piece.” “In terms of.” “Fair enough.” School was supposed to be a workshop, not a reliquary. But I don’t blame students entirely. I blame the unspoken expectations. I suspect everyone felt it too: you should have a show before you graduate. It poisoned every possible constructive step in the process. Because there was no room for growth. We were pretending to be finished.